Sourbread times and temperatures

Sourdough Bread: Times and Temperatures

Author: Martin Earl

There’s nothing like freshly baked bread to make your home smell amazing. Everyone loves a fresh, warm loaf spread with softened butter and maybe some quality jam. But bread is intimidating for many people to make, and so most of us rely on the store-bought stuff. And while I’m not here to criticize sliced bread, I do think that reexamining the ease with which you can make quality artisan-style bread is worthwhile. In this post, we’ll examine the mechanics of sourdough baking, including the need for both time and temperature awareness in making easy, fantastic sourdough bread.

SOURDOUGH BASICS

Sourdough bread is made in six basic steps:

We will deal with each of these in turn. (Or you can skip straight to the recipe for sourdough bread.)

SOURDOUGH STARTER/LEVAIN

Suffice it to say that sourdough is made by using a culture of wild yeasts and bacteria that work together to form the gasses and flavoring elements that give sourdough its texture and flavor. That symbiotic colony of microscopic bugs lives in what we call a starter—a mixture of flour, water, and the fungi and bacteria we need for that characteristic sourdough taste.

Keeping a starter alive is much like keeping a pet alive. You need to feed it and make sure it is well groomed. The acids and alcohols that accumulate in a starter can actually kill off the microbes if left alone for too long, so it is important to dilute them with occasional feedings. Adding water and food to the starter brings down the alcohol/vol as well as raises the pH, plus it gives the microbes food to eat and reproduce. If the microbes aren’t properly fed and cared for, they can either die or, if refrigerated, simply go dormant.

That dormancy can be your friend, though! One thing that scares many people off from making sourdough themselves is the relentless feeding schedules prescribed by most books on the subject. But if you have made your sourdough loaf and don’t plan to make more for another week, stick your starter in the fridge: it will go dormant and can be reawakened by feeding it when you need it. The starter is best fed with a mixture of equal parts water and flour as measured by weight and, if you really want it to be happy, make a portion of that flour rye sourdough—microbes just love rye flour!

Technically speaking, though, the starter itself is not what you put in your dough to make sourdough bread. What you really need is a levain made from your starter.

Because [the] natural yeasts may be less concentrated in the starter, a second stage mixture called a levain is prepared to add more yeast food and encourage yeast activity.”

On Baking, by Labensky, Martel, VanDamme, pg 181

A starter can be dormant, but a levain is an awakened, super-charged version of a starter that has new food for the yeast added to it so that it has the metabolic momentum needed to make bread faster. A levain is, in essence, a freshly-fed starter.

To prepare a levain, remove some starter from the refrigerator 3-12 hours before you wish to start making the dough (as little as just a few tablespoons will do, but more is better) and feed it with 100 grams each of flour and water. Leave it on the countertop during this time.

When you use the levain for baking, reserve some of it in its container and feed it again before putting it back in the refrigerator.

AUTOLYSING

The French Baker Raymond Calvel developed a novel addition to the process of bread making that he called autolysis. In this step, the flour is mixed with the water and allowed to sit for a time. This results in a more even hydration in the dough, but it also allows the natural enzymes in the flour to breakdown cells and other structures within the flour granules. (Autolyse comes from the roots “auto,” meaning self, and “-lyse” meaning to break down.) This breakdown makes gluten molecules more readily available in the dough and improves its flavor, texture, and workability.

To improve the autolysis, use water that is between 80° and 85°F (27° and 29°C). That temperature range is ideal for the enzymes in the flour to be active. Scalding water would destroy the enzymes, while cold water would slow them down.

The autolysing step usually lasts for 20 minutes, but it can last longer.

If the autolyse, or rest, is more than 30 minutes, the yeast is added later so that it doesn’t start to ferment before mixing.”

The Bread Bible, by Rose Levy Beranbaum, pg 55

In this version of sourdough, we mix the levain with the flour and water before the autolyse step, but we keep the resting period to 30 minutes. This allows the yeast to start interacting with the flour earlier in the process, speeding the later fermentation a little bit.

FINAL MIXING AND FOLDING

Once the autolysis is finished, the salt and the rest of the water is added to the dough and mixed in. For artisan-style bread, this is usually accomplished via a “pinching” motion: using bare hands, you reach into the dough and pinch a large chunk between your thumb and forefinger, cutting through it. This is repeated all through the dough, paying attention to lumpy bits in particular. Once the dough has a uniform-though-sticky texture, mixing is complete.

You may be wondering when the kneading happens. It doesn’t. Rather than kneading the dough to develop the gluten, it is repeatedly stretched and folded. The stretching and folding action pulls the gluten strands and helps them to form the net that will catch the gas bubbles from the yeast to help the loaf rise.

For the folds, set the bowl with the dough in it in front of you. Think of the dough as a map, with north at the ‘top.’ Pull the ‘northern’ most edge away from yourself, stretching it, and fold it back onto the dough lump. Do the same with the southern, eastern, and western edge of the dough ‘map.’ (The first set of folds counts as part of the mixing for the sake of our counting in this step.)

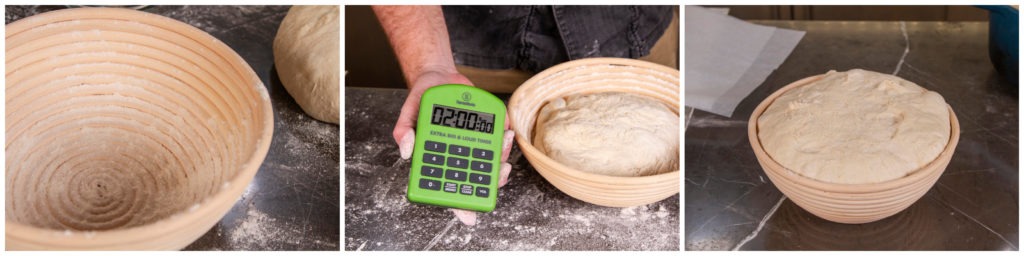

Let the dough rest, covered, for 30 minutes. A loud kitchen timer like our Extra Big and Loud will allow you to move about the house and still hear the timer going off. After 30 minutes, fold the dough again in the same way: north, south, east, west (the order doesn’t matter). Set the timer again and allow it to rest. This folding and resting is performed four times after the mixing—or five times if we count the first folding at the end of mixing. With each fold, you will notice that the lump becomes firmer and less loose. That is because of the gluten development that is happening in the folding process.

After the fourth and last folding, you can go right into the next step without waiting another 30 minutes.

BULK FERMENT

This brings us to the bulk fermentation stage, known popularly as ‘rising.’ In this stage, we allow the bread to rise as a whole lump, hence the ‘bulk’ in the name. In this stage the yeast metabolizes sugars in the dough, producing carbon dioxide, alcohol, and various flavor compounds. The speed and metabolic efficiency of the yeast depend almost entirely on temperature, with the optimal speed of fermentation occurring between 80–90°F (27–32°C).

That temperature is optimal, but you can get a faster rise with warmer temperatures (to a point) or a slower rise with cooler temps. But there is a trade-off. When yeasts are warm and happy, they metabolize efficiently, meaning they convert the sugars well, without many byproducts. But the byproducts of inefficient metabolism taste great. For richer flavor, it can be useful to slow down, or retard, the fermentation. This is often done by putting your dough in the refrigerator for the bulk fermentation, or even later on, during the proofing.

The actual fermenting time will depend on temperature and on the activity of your yeast. While you cannot really control the activity of your strain of yeast, you can control its metabolism with temperature. A good idea is to make a batch of bread and let it rise at room temperature, using your ChefAlarm® to record the temperature of your kitchen, then base your sped-up or slowed-down rise times on that temperature.

It is helpful to know when estimating rising time according to room temperature that the rate of fermentation, or rising, is about double for every 15°F [8°C] increase in temperature.”

The Bread Bible, pg 62

With your room-temp baseline rate of fermentation established, you can adjust its speed accordingly. Because not only is the rising time twice as fast for every 15°F (8°C) increase in temperature, it is also twice as slow for every comparable decrease in temperature. So if the yeast in your dough takes, say, one hour to rise at 70°F (21°C), it should take two hours at 55°F (13°C), and four hours at 40°F (4°C). Again, your ChefAlarm or one of our dedicated fridge thermometers can tell you the temperature of your refrigerator, so you can better time a slower or faster rise based on your room-temperature rise.

Whether you go for flavor or for speed, your dough should rise until it has increased in bulk by about a third.

SHAPING AND PROOFING

Once you have finished the bulk fermentation, it’s time to shape and proof the loaves.

To shape them, flour your work surface and turn your dough out onto it. Release any clingy bits from the sides of the bowl and add them to the lump. The recipe that follows is enough for two large loaves or four small loaves. Once you decide how many loaves you want to make from your recipe, divide the lump into the corresponding number of smaller lumps. To shape them into a classic round shape, place one lump of dough in front of you and basically perform another stretch cycle on it: pull the ‘north’ side away from you and fold it onto the top of the lump, then the ‘east’ and ‘west’ sides, then the bottom or ‘south’ side.

Turn this newly taut loaf so that the seam side is down.

Pick it up and tuck the dough from the bottom edges towards the middle of the bottom, creating tension on the top of the loaf. Then place it back on the floured surface and, using a bench scraper, slide it under the lump, tucking and rotating it to make it round lump and to give the top even more tension.

To prepare it for its final proof—the rise that is done when the dough is shaped—liberally sprinkle some cane baskets or bowls lined in cloth with rice flour. Place your loaves, seam side up, in the baskets/bowls. (The rice flour acts as a barrier to gluten formation and keeps your dough from sticking to the bowl.)

To proof them, let them sit, covered, at room temperature for up to 3–4 hours, or let them proof for a little while at room temperature and then place in the refrigerator for 12–15 hours. Or you can speed the process by using a proof box, warm cooler, or slightly warm oven to speed things up. Again, how long to proof will depend on your yeast strain and your proofing temperature, so try it at your room temperatures and adjust the proofing temperature accordingly. We used a cooler with a few inches of warm (100°F [38°C]—thanks, Thermapen®!) water in the bottom and the proofing took about two hours.

To tell if the proofing is complete, press on the dough with your thumb. The print you make should partially spring back but not completely. If it springs back readily, it needs more time, if it stays completely sunken, the dough is over proofed. It should also be about 30-40% bigger than it was when you started proofing.

BAKING SOURDOUGH

While the bread is proofing, preheat your oven to 500°F (260°C) with a lidded cast iron pot inside of it for an hour. Why the cast iron pot? For steam! Professional bakeries have specialized ovens with steam injectors that keep the baking environment very humid, and that humidity is critical for developing a glossy, golden, crisp crust. Many bread cookbooks try to mimic this by putting a pan of boiling water in the oven with the bread, but most home ovens are vented exactly to prevent steam from building up inside of them. By using a heavy, heat-retaining pot with a lid, you can create a steamy environment for your bread to bake. The water from the dough that turns to steam is captured in the pot, and the all-around heat provided by the hot pot itself is also advantageous to the cooking process.

Once the bread is proofed and the oven and pot are well heated, it’s time to bake. Remove a loaf from the proofer and place a sheet of baking parchment paper on top of it. Quickly turn the basket upside down onto the countertop, and lift the basket off of the dough. Beautiful!

See how much it’s risen…

See how much it’s risen…

For the loaf to be able to handle the oven spring without tearing itself apart, it needs to be slashed. Use a razor or a very sharp knife to cut slashes into the top of the bread. A slashed square around the crown is a great way to go and will provide nice ‘ears’ on the loaf later. (Ears are the bits of bread that stick out, ledge-like, from the body of the loaf. They are extra crispy and delicious.) Once the dough is slashed, remove the pot from the oven very carefully and place it on a heat-proof trivet or hot pad. Remove the lid, pick up the sheet of parchment by the sides, and lower the loaf, parchment and all, into the pot. Place the lid on the pot and put it back in the oven.

Once the pot is in the oven, turn the heat down to 475°F (246°C) to bake. Set a timer for 20 minutes.

After 20 minutes, get your ChefAlarm and set the high alarm to 200°F (93°C). (Lean dough breads are done between 190–210°F [88–99°C], and dough with this level of hydration is also best done around that temperature. You can, of course, decide how you like your bread done and cook it to that temperature every time with a little experience!) Open the pot in the oven and stick the probe from the ChefAlarm into the center of the bread. At this point the oven spring will be finished, so the bread will have enough structure to handle the sudden loss of heat and will be able to support the probe within itself.

Continue to bake the bread, with the lid off to brown the crust and deepen its flavor. Cook it until your ChefAlarm sounds and verify the temperature in the loaf with a Thermapen to make sure the bread is entirely above 200°F (93°C) throughout.

Note: Unless you have multiple ovens or a very LARGE oven, you will need to cook your bread batch-wise. When you put your first loaf in the oven, take the second loaf out of the proofing box, if you were using one, so that the proofing slows down for the roughly 30 minutes of baking that will occur. When the first loaf is nearly up to temp, prepare the second loaf on a sheet of parchment, etc.

Also, when you remove the lid while baking your first loaf, keep it in the oven so that it’s still hot for the next loaf. You needn’t heat the pot to 500°F (260°C) between loaves, the heat from the previous cook will be enough.

To prevent the bottom of your loaf from overcooking and becoming unenjoyably tough, use a pizza or baking stone on the rack below the one you’ll be cooking on. This acts as a buffer against the heating elements of the oven, evening out the heat that the pot experiences. Once your loaves are done, let them cool on the counter for at least an hour, if you have that kind of will power.

This whole process may seem arduous when you first read it, and even when you first try it, but once you’ve done it once or twice, it’s really not that hard. Yes, there are a lot of steps, but none of them are particularly difficult. With some practice, you can find ways to split this process up so that it fits into your schedule, allowing things to ferment overnight or proof overnight, baking in the morning, etc. With a little trial and error, you can start to work perfect, delicious homemade bread into your daily routine.

BASIC COUNTRY SOURDOUGH BREAD RECIPE

Based on Tartine Sourdough Recipe, Slightly Modified, by The Perfect Loaf

INGREDIENTS

- 740 plus 50 grams water at 85°F (29°C)

- 200 g levain (sourdough starter)

- 700 g bread flour

- 200 g all-purpose flour

- 100 g whole-wheat flour

- 20 g salt

INSTRUCTIONS

AUTOLYSE

- Combine the levain and the 740 grams of water. Use a Thermapen to make sure the water is at the 85°F (29°C)

- Add half of each of the flours to the levain-water mixture and combine to form a smooth batter.

- Add the rest of the flour to the batter and mix it until it is a shaggy mass with no dry lumps visible.

- Allow the dough to rest, covered, on the counter top for 30 minutes. This will allow the natural enzymes in the flour to create a more easily workable and shapeable dough that will have a better texture.

-

MIX FINAL DOUGH

- Uncover the dough and sprinkle the salt evenly over the surface.

- Add the remaining 50 grams of water, also at 85°F (29°C), wetting all the salt.

- Mix the dough by squeezing and pinching it between your thumbs and fingers. Continue until you feel no lumps in the dough.

STRETCH AND FOLD THE DOUGH

- Fold the dough by pulling the back or furthest part of it away from you, then folding the stretched part back onto the lump. Do this a total of four times, pulling and folding the dough in each of the four directions.

- Cover the dough and set a timer like the Extra Big and Loud Timer for 30 minutes.

- After 30 minutes, uncover the dough and perform another set of folds, one forward, one back, one left, one right on the dough. (This is made easier by first wetting your dough-handling hand. Less dough will stick to you this way.) You should notice that it makes a slightly more defined lump. This counts as your first fold

- Repeat this process three more times, stretching and folding the dough every 30 minutes. Not counting the initial fold after mixing that makes four folds.

BULK FERMENT

- Cover the dough and let it rest in a warm place (80–90°F [27–32°C]) for 1 hour, until it has risen by about 30%.

DIVIDE AND SHAPE

- Flour a work surface.

- Tip your dough out onto the surface and scrape as many bits free from the bowl as possible.

- With a bench scraper or sharp knife cut the dough into two equal halves.

- Working with one lump, created the shape and some surface tension on the bread by basically doing another fold: pull the part that is farthest from you out away from you and then fold it in onto the top of the lump.

- Do the same for the sides and the part nearest you.

- Turn the dough over and pull and tuck the edges in under the loaf, creating tension on the surface of the loaf.

- Repeat with the other loaf.

- If you have proofing baskets, sprinkle them with rice flour. If not, line two bowls with cloths (such as a cotton or linen napkin) and sprinkle the cloths with rice flour.

- Place the loaves seam-side up in the bowls/baskets.

PROOF THE LOAVES

- Place the loaves in a warm place to proof for as little as one hour in an oven with a proof setting or a cooler with a few inches of hot water in the bottom of it. Your proof-box should be between 75° and 85°F (24° and 29°C). They should rise and feel airier, but not be completely inflated. They can also proof in the refrigerator overnight. (See section on proofing times above.)

SCORE AND BAKE

- While the bread is proofing, preheat your oven to 500°F (260°C) with a lidded cast-iron pan inside.

- (Note: your bread will bake better if you have a baking stone on the oven rack below your bread. It will act as a buffer against the heating elements in the bottom of your oven.)

- Once the bread is proofed, turn it out onto a piece of parchment paper.

- Score the top of the loaf with a sharp knife or a razor blade, cutting a square around the crown of the bread.

- Remove the cast-iron pot from the oven.

- Lift the parchment paper with the bread on it and lower it carefully into the cast iron pot.

- Place the lid on the pot, put it in the oven, and lower the oven temperature to 475°F (246°C).

- Set a timer for 20 minutes and bake.

- Once 20 minutes has elapsed, set your ChefAlarm to 200°F (93°C), remove the lid from the pot and insert a probe into the center of your bread.

- When the alarm sounds on your ChefAlarm, verify the temperature with your Thermapen.

- Remove the bread from the oven and place the new, uncooked loaf in the pot, following the same method for cooking it.

- Allow the bread to cool on the countertop for at least an hour.

- Slice, or just tear the bread into chunks, eating it with plenty of good, salted butter and jam.

Sourdough bread needn’t be something to fear or be mystified by. It’s just a matter of times and temperatures—and with The Extra Big and Loud timer, the Thermapen®, and the ChefAlarm, you can be sure that your times and temps are going to be right every time. Skip the line at the bakery and get quality, artisan-style bread in your own kitchen

Go ahead if you like it tell your friends

Tell us too

Related Content

New Comment ...